Cleaning your CPAP machine can feel like a hassle, but it’s worth the effort. Regularly washing the mask, hose, and other components of your CPAP machine by hand prevents harmful bacteria, viruses, and fungi from growing in them.

Over the last several years, a number of CPAP cleaning devices that claim to efficiently and effectively sanitize CPAP components have come onto the market. However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has yet to authorize any of these products. In fact, the FDA cautions against using them.

Learn more about which CPAP cleaning methods are okay to use and which are best to avoid, according to the FDA.

Think You May Have Sleep Apnea? Try an At-Home Test

our partner at sleepdoctor.com

Save 45% on your Sleep Test Today

Shop now“Truly grateful for this home sleep test. Fair pricing and improved my sleep!”

Dawn G. – Verified Tester

What Is a CPAP Machine?

A continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine helps a person breathe while asleep. These devices are one of the primary treatments for sleep-related breathing disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and central sleep apnea (CSA).

CPAP machines work by pumping pressurized air from a machine through a hose and into a mask covering the nose and mouth. The pressurized air prevents the narrowing or collapse of soft tissues in the throat, keeping the airway open.

Why Does a CPAP Machine Need to Be Cleaned?

CPAP machines need regular cleaning to remove germs, dead skin cells, and oils that accumulate in and on the hose, mask, headstraps, and other components. Not cleaning your CPAP machine often enough could have several negative consequences, including:

- Reinfecting yourself with an illness, such as a cold

- Getting a bacterial or fungal infection

- Developing skin irritation

- Accelerating the breakdown of mask components and affecting its seal

To avoid these problems, stick to a regular cleaning schedule for your CPAP machine.

How to Clean Your CPAP Machine

It is best to refer to your CPAP device’s instructions for cleaning. Most manufacturers recommend washing the CPAP components by hand with mild soap. You may also use one part white vinegar diluted with three to four parts water, which can help reduce odors.

Never use cleaning products that leave a residue or contain harsh chemicals like bleach. Do not boil CPAP parts or clean them in a washing machine unless instructed to do so by the manufacturer. And make sure to unplug your machine before cleaning it.

While cleaning instructions may vary by model or manufacturer, there are some recommended practices that are similar across most devices.

| CPAP Component | Recommended Cleaning Frequency | Cleaning Instructions |

|---|---|---|

| Nose pillows or cushions | Daily |

|

| Mask | Every other day |

|

| Headgear and chin strap | Weekly |

|

| Hose or tubing | Weekly |

|

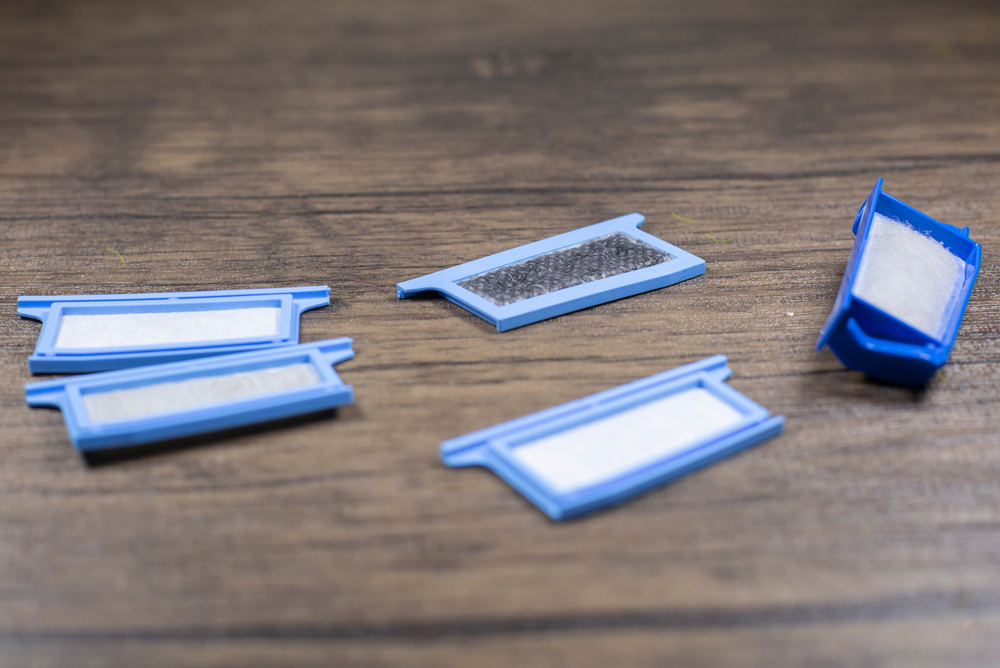

| Reusable foam filters | Weekly |

|

| Humidifier chamber | Weekly |

|

| CPAP machine | As needed |

|

In addition to following these instructions, you can discourage the growth of germs by disconnecting and hanging up the tubing of your CPAP machine on the mornings you don’t wash it. Also, consider using distilled water in the device’s humidifier, which will limit mineral buildup.

When in doubt about how to clean your device, contact your CPAP machine’s manufacturer or a healthcare provider.

Additionally, remember to check your CPAP supply replacement schedule, which is typically provided by your CPAP machine’s manufacturer. This schedule generally recommends replacing CPAP parts—such as the hose, mask, mask cushion, filter, and humidifier chamber—every one to six months.

If you have questions about reimbursement for CPAP supplies, you can contact Medicare, your insurance provider, or a durable medical equipment provider for more information.

CPAP Cleaning Products That Are Not FDA-Approved

In recent years, a number of companies have begun selling devices that claim to clean CPAP accessories more efficiently and more effectively than hand washing them. Marketed as being able to disinfect or sanitize CPAP components, these products use ozone or ultraviolet (UV) light, typically inside a box-shaped device or a bag.

The FDA has been conducting research on these products, as well as monitoring adverse events associated with them. Currently, the FDA cautions against using these products to clean CPAP devices and accessories until it determines that they are effective at killing germs and safe to use.

Ozone Gas Cleaners

Ozone is a gas consisting of three oxygen atoms. It occurs naturally in the atmosphere and is also present in pollutants such as smog. For decades, water treatment plants have used ozone to disinfect drinking water, and in medical settings, it is used to sterilize reusable medical devices.

However, exposure to ozone gas is harmful to human health. Contact with ozone can cause a range of symptoms, from coughing to headaches, and in the long term, it can cause asthma.

Ozone levels necessary to clean CPAPs may be dangerous. Manufacturers and sellers of ozone CPAP cleaning devices claim that their products contain the toxic gas within a sealed chamber, limiting the user’s exposure to it. However, they do warn that CPAP supplies need to be ventilated after being treated with ozone to prevent ozone from remaining inside of them.

UV Light Cleaners

UV light is naturally produced by the sun and artificially produced by certain types of lighting. Some at-home systems use UV light to purify drinking water, and in medical facilities, UV lamps have long been used to disinfect surfaces.

As anyone who has ever spent too much time in the sun knows, directly exposing the skin to UV light can cause irritation and even burns. Most CPAP cleaning devices that use UV light automatically turn off the light when the door of the device is open, but the FDA has not verified that this provides sufficient protection from UV exposure.

What Is the Concern About Some Devices That Claim to Clean CPAPs?

The FDA has warned that CPAP cleaning devices may not be as effective or as safe as they are marketed to be.

As manufacturers and sellers of these devices acknowledge, ozone and UV light cannot remove grime or oil from the surface of CPAP accessories. Because washing by hand is still necessary for removing buildup, these devices do little more than add an additional step to the cleaning process.

Moreover, the FDA has warned that both ozone and UV light CPAP cleaning devices pose risks to users.

Risks Associated With Ozone CPAP Cleaning Devices

The FDA has found that ozone can leak from CPAP cleaning devices, creating the potential for unsafe levels of ozone. The FDA has also tested some of these products by running them in small bathrooms. For several models, ozone levels within the room have exceeded safety standards following device operation.

Moreover, the FDA has discovered that ozone can stay in CPAP tubing for hours after cleaning if fresh air is not circulated through it. This means that users could unknowingly inhale ozone after cleaning their CPAP machines.

Some people have reported concerning symptoms after using ozone CPAP cleaning devices, including:

- Headaches

- Coughing

- Asthma attacks

- Trouble breathing

- Sinus irritation

Exposure to ozone from these devices could increase a person’s risk of getting a respiratory illness or aggravate chronic conditions like asthma.

Risks Associated With UV Light CPAP Cleaning Devices

There have not yet been any reports of UV light from CPAP cleaning devices causing injury. That said, the FDA warns that inadvertent exposure to UV light from these products has the potential to harm the eyes or skin and even elevate the risk of skin cancer.

Additionally, the UV light generated by these devices may not reach the interior surfaces of CPAP accessories, such as the hoses. As a result, germs could remain, putting the user at risk of an illness or infection.

Reporting a Problem With a CPAP Device

The FDA collects information about adverse events related to medical devices, including CPAP equipment. If you experience an issue with your CPAP machine or a CPAP cleaning device, consider reporting this issue to FDA’s MedWatch Online Voluntary Reporting Form.